Charlie Abbott, Associate Lecturer, BA (Hons) Graphic Design, Camberwell College of Arts

Issues around sustainable development are characterised by the complexity of interactions between social and ecological systems, a complexity that is underrepresented by diagrammatic representation and only partially comprehended through single disciplines. This paper seeks to address this by exploring how models of Co-Design and Experiential Learning can encourage multi-disciplinary engagement with, and reflection upon, issues around sustainable development. Using the Graphic language of ‘Ideograms’, a 45 minute workshop was developed that encouraged participants to create pictorial representations of issues around sustainability of personal significance. The resulting focus group discussion highlighted the iterative processes key to Co-Design, and its effectiveness in encouraging debate and reflection upon sustainability issues.

experiential learning; co-design; sustainable development; graphic design

This article contains a summary of the definitions of ‘Sustainability’ and reading around Education for Sustainable Development that informed my understanding of the subject in relation to my discipline, Graphic Design, and my teaching of it. This research resulted in the development of a 45 minute workshop that explored some of these ideas through the production of ‘Ideograms’, defined as a ‘character which symbolises an idea by representing an associated object but does not express sounds of its name’ (Garland, 1980, p.84). The results of the workshop are discussed here using excerpts from a focus group conducted with its participants.

Whilst models of Sustainability and ‘Sustainable Development’ vary considerably in their interpretation of the subject, the core components that comprise its definition can be said to be largely agreed upon: ‘each emphasises that activities are ecologically sound, socially just, economically viable and humane’ (Clugston and Calder, 1999, p.33). Dawe, Jucker and Martin provide a similarly concise description, with three key criteria that define sustainable activity as ‘social progress which recognises the needs of everyone’, the ‘effective protection of the environment’ and ‘prudent use of natural resources’ (Dawe, Jucker and Martin, 2005, p.52).

For the most part, these descriptions of Sustainability can be seen as reactions to a world ‘characterised by fluidity, complexity, uncertainty, and indeed, unsustainability’ (Sterling, 2012, p.14). It is unsurprising, therefore, that the concept of Sustainable Development arose in response to this uncertainty, as an over-arching system of ideas that describe ‘the processes and activities that help ensure social, economic and ecological wellbeing’ (Sterling, 2012, p.10).

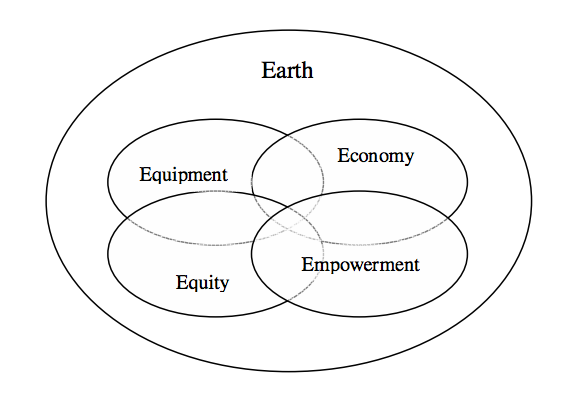

If the initial aims and descriptions of Sustainability and Sustainable Development seem to largely reach a consensus, there exists much debate around visual ‘models’ of their interpretation and application. Whilst the ‘Three-Legged Stool’ definition (Figure 1) is a widely used and recognised framework, it has encountered much criticism due to the implication that ‘all three elements [Economy, Environment and Society] are equally important and interact on the same level’ (Dawe, Jucker and Martin, 2005, p.53). Moreover, the exclusion of cultural activity from the model has been seen as a fundamental omission. As Keith Nurse states, ‘culture shapes what we mean by development and determines how people act in the world’ (2006, p. 37).

Contemporary conceptions of Graphic Design tend to emphasise its potential for solving complex, systemic problems, as well as providing a series of communication strategies capable of traversing social, political and disciplinary divides. As such, Sustainability is a ‘view of design which is about living in the world as a human being which requires a recognition of socio/political contexts which integrate with design’ (Davies, 2002).

This emphasis on integration between different contexts suggests that a ‘nested’ model of Sustainability might act as a more appropriate background on which to embed and explore Graphic Design principles and practice. To this end, the ‘5-element’ nested model put forward by Dawe, Jucker and Martin in 2005 (Figure 2) appears to most satisfactorily indicate the relationships between each aspect, or sphere, of Sustainability. Culture, in this instance, can assist in expressing the manner in which the spheres interact and how information is generated and passed between them.

Whilst convenient, model-based based definitions of Sustainability run the risk of underrepresenting the myriad issues and challenges that surround the subject, in particular Graphic Design’s relationship to it. Henry writes that the ‘problems of sustainability typically arise from the complex interactions between social and ecological systems’ (Henry, 2009, p.133). It is the complexity of these interactions and their effect across a range of contexts that has led Sterling to assert that Sustainability ‘cannot be understood adequately through single disciplines’ (2012, p.36). Yet at the same time, there exists a perception that design is still taught and practiced in isolated disciplines, or ‘silos’. According to Park and Benson, ‘silos of practice stand in opposition to the type of creative processes and collaborations necessary to help solve the issues that humanity faces today’ (2013, p.1). Furthermore, whilst ‘employing a systems thinking methodology’ (Park and Benson, 2013, p.3) to problem solving is often portrayed as a central tenet of Graphic Design practice and education, there is the possibility that in the case of Sustainability, systemic, rational conclusions and models may prove a diversion away from core issues, particularly when situated within an equally systemic assembly-line model of production. The emergence of the ‘Agency’ model of Graphic Design throughout the twentieth Century did much to reinforce and compartmentalize the production of designed artefacts along Fordist principles, ‘in each of these cases, a system of vertical integration was sought according to divisions of labour […] within each of these teams one would find sub-specialisms’ (Julier, 2008, p.31). Increased pressures on resources have prompted many contemporary Graphic Designers to subvert this model in search of more sustainable, interdisciplinary practices (see, for example, Dexter Sinister and the production of Dot, Dot, Dot magazine, 2007). As Bell and Russell observe, ‘teaching about ecological processes and environmental hazards in a supposedly objective and rational manner is understood to belie the fact that knowledge is socially constructed and therefore partial’ (2000, p.199).

If the traditional assembly-line model of Graphic Design poses barriers for teaching Sustainability - in its perception of entrenched disciplinarity and an overtly rational, systemic description of the world[1] - there exist a number of strategies through which a more meaningful learning experience can be achieved.

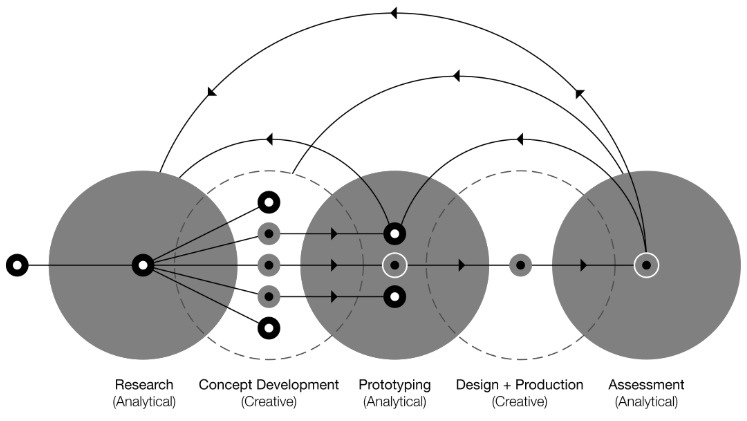

Co-Design (as a facet of co-creation) is increasingly highlighted as a strategy for increased inter-disciplinarity within the design process, ‘espoused […] as one of the primary means for transformation of the dominant worldview that is taking place today’ (Sanders and Stappers, 2008, p.5). Co-Design disrupts the traditional linearity of the design process (Figure 3) by involving a diverse range of stakeholders in the design of the product or piece of communication from the start: ‘the researcher (who may be a designer) takes on the role of facilitator’ (Sanders and Stappers, 2008, p.11), in the belief that more critically engaged, widely informed and empathetic solutions will arise.

Sterling asserts that Education for Sustainability ‘requires active, participative and experiential learning methods’ (2012, p.36). In many ways, Graphic Design education - as ‘a field of concern, response and enquiry, as often as decision and consequence’ (Potter, 2002, p.32) - is well suited to meet Sterling’s requirements, through an emphasis on learning through the process of making and critical reflection. That said, the rarefied atmosphere of producing Graphic Design within a university context can lend a level of abstraction to students’ understanding of Sustainability. This perception is counter to Bell and Russell’s assertion that Sustainability ‘calls for educational practices [to be] situated in the life-worlds of students’ (2000, p.198). If an aim of Education for Sustainability is to ‘enable students to seek solutions in an adequate and non-reductionist manner for highly complex real life problems’ (Dawe, Jucker and Martin, 2005, p.58), it therefore seemed logical to look to an Experiential Learning model when addressing some of these aforementioned issues in a workshop on Graphic Design and Sustainability.

Entitled ‘Pictorial Construction - Pictorial Speech?’, the workshop explored principles of Co-Design and inter-disciplinarity to encourage ‘explorations in the front end’ of the design process (Sanders and Stappers, 2008, p.13). This was further suggested by the restrictive nature of the materials provided in the workshop brief (Appendix 1). This subject - a Sustainability issue of personal significance - was selected to support ‘the integration of personal values into the process of designing’ (Benson and Napier, 2012, p. 206) as a response to Henry’s call for ‘individuals […] to understand the realities of a complex and uncertain world’ (2009, p.133), away from the sometimes hypothetical environments of the University.

The structure of the workshop involved group discussion that led to identification of a subject, a process that was then transformed into an Ideogram, the effectiveness of which was discussed amongst the group. This method aimed to closely parallel Kolb and Kolb’s experiential learning cycle, in which learning is ‘enriched by reflection, given meaning by thinking and transformed by action’ (2010, p.27).

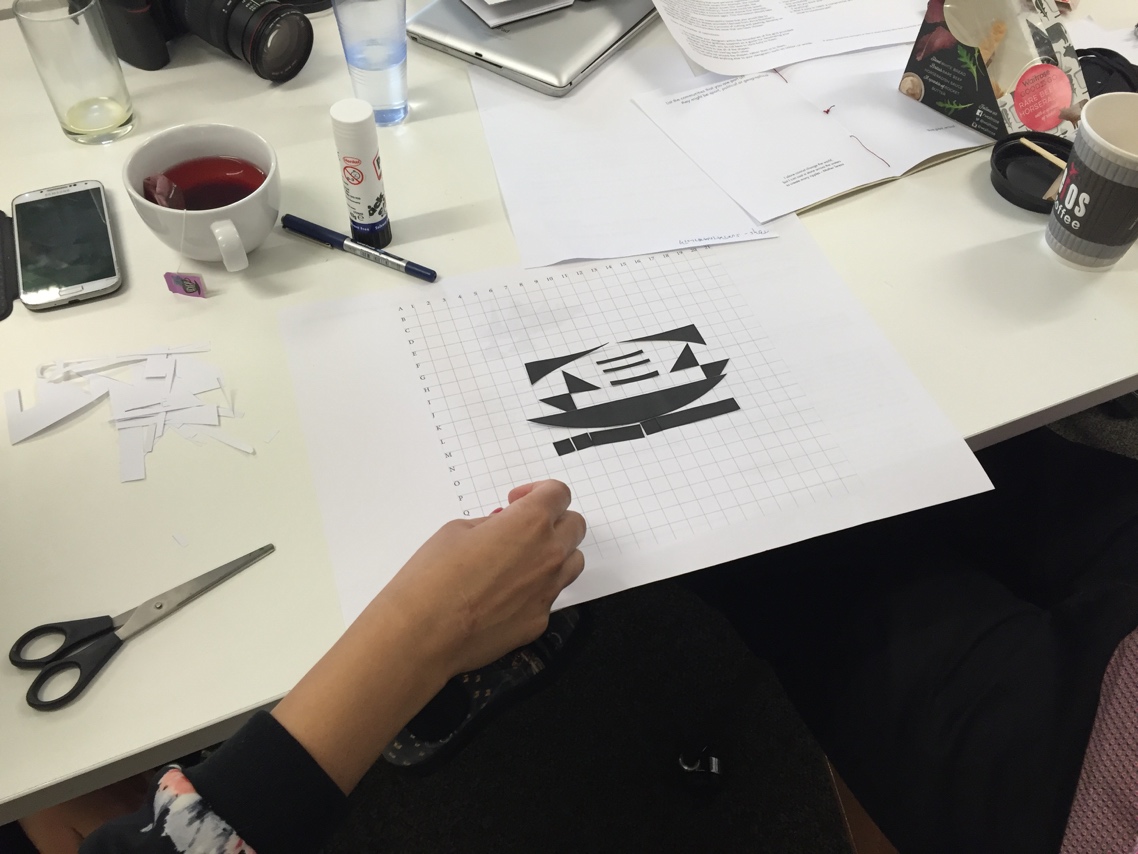

The modular aspect of the example Ideogram shapes provided in the brief aimed to encourage participants to ‘play’ with possible configurations before committing to their final, designed Ideograms. This responded to the fact that in models of Experiential Learning ‘an equal value is placed on the process and the outcome of learning’ (Kolb and Kolb, 2010, 47) and as a way of introducing reflection at the beginning of the design process. The act of producing the Ideogram was chosen in order to meet Benson and Napier’s call for ‘visualisation and reflection as a way to connect personal values and holistic value systems in order to make responsible, sustainable design decisions’ (2012, 197).

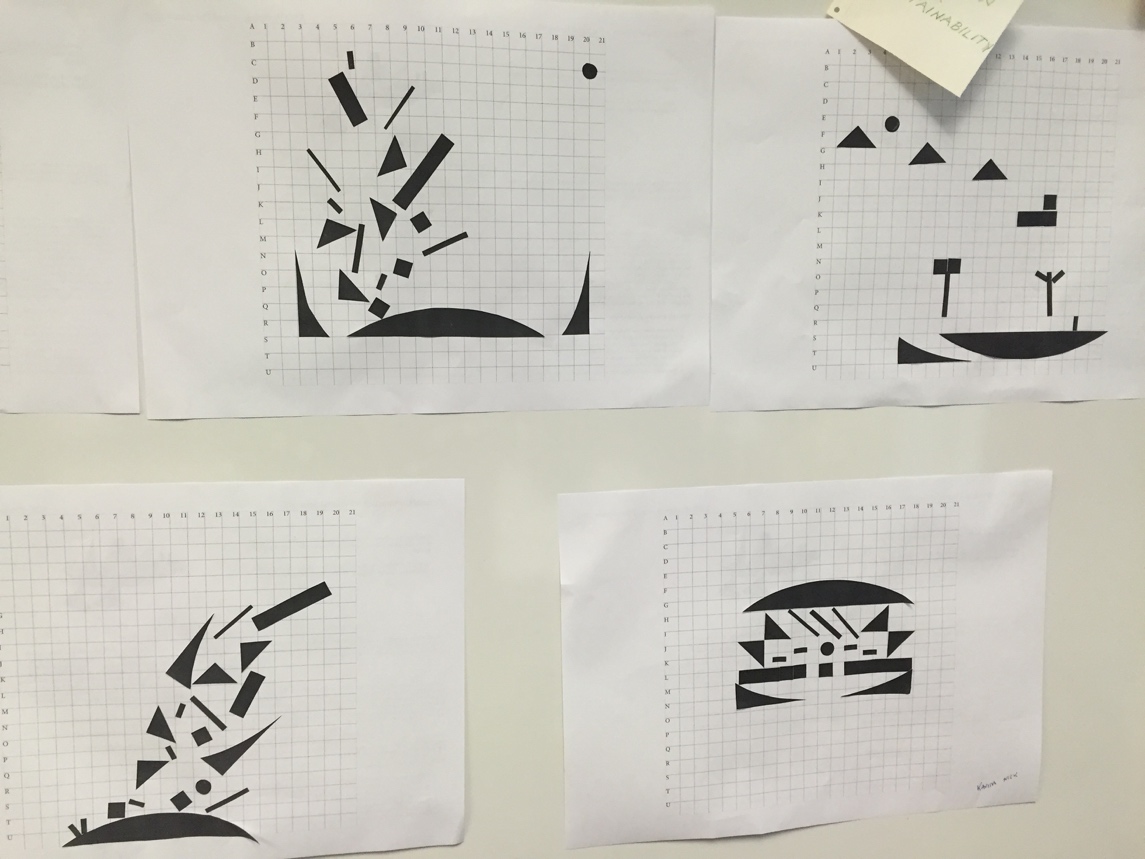

The results produced during the workshop varied considerably, both in the scope of the subject matter depicted as well as the approach that each group took towards the production of their Ideograms. As indicated by focus group discussions on the workshop, held at UAL on the 2nd December 2015, the Sustainability issues selected by participants ranged from broader philosophical concerns, ‘the ability to think about yourself interconnected to the surrounding world’, to specific examples of unsustainable practices, ‘I have personally got an issue with packaging in general […] sometimes there is just too much there’ (comments from focus group transcript).

Regardless of the scope of these comments many participants felt that the act of having to define a Sustainability issue collaboratively, encouraged a wider internal debate around the subject. One participant remarked that ‘it was good because we had a long discussion’ prior to forming their designed Ideogram, whilst another group found that the act of making and talking occurred simultaneously: ‘we were playing with making images, the way that you can […] change them and discuss what is happening’.

This approach used the process of forming Ideograms to evoke discussion around possible sustainability issues.[2] It seemed to be favoured by many of the groups that took part in the workshop, with one participant describing their design process as follows:

“the shapes are great, because you can[…] it changes the way that you think when you’re moving things as well, because its giving you ideas, rather than sitting here with a blank piece of paper, there is [...] a two-way thing going on.”

This student describes a ‘two-way’ relationship between the subject matter and the form of the Ideogram, demonstrating the extent to which participants used the process of completing the task to reflect upon what they intended to communicate. In this sense, the participants could be said to be conforming to the emphasis on play that is key to Experiential Learning, in which the ‘outcome acquires meaning only if equal attention is paid to the experience and the process of play’ (Kolb and Kolb, 2010, p. 47). In many cases, the outcome for each group was the result of a reflective and iterative process - ‘it just came to me, [while] moving them around’ - rather than the systemic realisation of a fixed idea. This indicates that many participants were flexible and open to negotiation when sharing issues of personal significance with one another.

Once this exercise was finished, the necessarily abstract nature of the final Ideograms themselves provoked further discussion around possible interpretations as to their meaning. One participant discovered new interpretations within their own design:

“You can almost see that as a mistake, I forgot to cut some out and there was a spare one, but what I’m now looking at it as a circle, it’s almost got that symbolism of the sun and the wholeness of the circle.”

In this instance, reflecting on the final design suggested new readings and points for discussion: something that participants also demonstrated when reviewing each other’s Ideograms. In one example, an image of a sandwich was given wider relevance, ‘but the hamburger is a symbol of culture isn’t it? The economy, the excess of meat’. By presenting, reflecting upon their final Ideograms and finding new discussion points, the participants came closer to completing the conventional model of the Experiential Learning cycle, which is ‘fully engaged by allowing players to come back to the familiar experience with a fresh perspective’ (Kolb and Kolb, 2010, p. 47).

The mutability, or at least the possibility of the Ideograms’ multiple meanings, goes some way to address Bell and Russell’s notion of the ‘socially constructed and therefore partial’ nature of knowledge (2000, p.199). Participants constructed meaning as a group, through shared reflection, narrative and experience. This process of co-creation can be seen as a foundation for social learning where ‘relevant knowledge and behaviours already exist: the question becomes how these objects of learning are diffused through a social network’ (Henry, 2009, p.135). Graphic Design, with its emphasis on the development of tools for communication, appears to be an appropriate system of ideas through which to promote such a diffusion, and thus a useful bridge between ‘those who produce relevant information [and] those who translate this knowledge into actual […] choices’ (Henry, 2009, p.134).

This report has demonstrated how my research around the subject of Sustainability and Education for Sustainable Development has identified a number of issues for the discipline and teaching of Graphic Design. Entrenched disciplinarity and the sometimes hypothetical context in which these subjects are taught within the University are two such barriers to student learning..This is exacerbated by the discipline’s tendency towards systemic, rationalised models of the world. This article has discussed an attempt to overcome these issues by developing a workshop based upon a model of Experiential Learning and Co-design, the Ideogram. This model was used as a means of encouraging reflection around the iterative process of designing and communicating, over the production of fixed artefacts.

Overall, the results of this workshop appear largely encouraging, with many participants responding positively to the challenge of inter-disciplinary collaboration and reflection. At the same time, towards the end of the workshop I felt reservations about the negative focus I had placed on Sustainability issues (or ‘problems’): examples of the ‘fatalistic handwringing’ deplored by many design writers (Sterling, 2005, p.13). A worthwhile extension of this workshop structure would be to invite future participants to suggest possible solutions to Sustainability issues. This workshop approach involved Speculative Design[3], which closely mirrors Experiential Learning, in that ‘the actual process of communication is at least as important as the fixed end result’ (Bruinsma in Sueda, 2014, p.32). Furthermore, inviting the same participants to return to the task again could fully enable the ‘fresh perspective’ that the Experiential Learning cycle calls for (Kolb and Kolb, 2010, p. 47).

Bell, A. C. and Russell, C. L. (2000) ‘Beyond human, beyond words: anthropocentrism, critical pedagogy, and the poststructuralist turn’, Canadian Journal of Education, 25(3), pp. 188-203.

Benson, E. and Napier, P. (2012) ‘Connecting values: teaching sustainability to communication designers’, Design and Culture: The Journal of the Design Studies Forum, 4(2), pp. 195-214. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/175470812X13281948975521. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/10228600/Connecting_Values_Teaching_Sustainability_to_Communication_Designers (Accessed: 18 November 2015).

Clugston, R. M. and Calder, W. (1999) ‘Critical dimensions of Sustainability in higher education’, in Filho, W. L. (ed.) Sustainability and university life. Frankfurt am Main; New York: Peter Lang, pp. 31-46.

Davies, A. (2002) ‘Enhancing the design curriculum through pedagogic research’, in Proceedings of 1st international conference - Enhancing curricula: exploring effective curriculum practices in design and communication in Higher Education. London: Centre for Learning and Teaching in Art and Design, CLTAD (UAL). Available at: http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/621/ (Accessed: 18 November 2016).

Dawe, G., Jucker, R. and Martin, S. (2005) Sustainable development in higher education: current practice and future developments. York: Higher Education Academy. Available at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/resource/sustainable-development-higher-education-current-practice-and-future-developments (Accessed: 18 November 2016).

Dot Dot Dot (2007) ‘Announcements’, Dot Dot Dot website. Available at: http://www.dot-dot-dot.us/index.html?id=33 (Accessed: 16 November 2016).

Flusser, V. (1999) The shape of things: a philosophy of design. London: Reaktion Books.

Garland, K. (1980) Illustrated graphics glossary used in printing, publishing, photography, and other fields of interest to graphic designers, their clients, and their suppliers. London: Barrie and Jenkins.

Henry, A. D. (2009) ‘The challenge of learning for Sustainability: a prolegomenon to theory’, Human Ecology Review, 16(2), pp. 131-140. Available at: http://www.humanecologyreview.org/pastissues/her162/henry.pdf (Accessed: 18 November 2016).

Julier, G. (2008) The culture of design. London: SAGE Publications.

Kahn, R. (2008) ‘From Education for Sustainable development to Ecopedagogy: sustaining capitalism or sustaining life?’, Green Theory and Praxis: The Journal of Ecopedagogy, 4(1), pp. 1-14. Available at: http://greentheoryandpraxisjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/Vol-4-Issue-1-2008.pdf (Accessed: 18 November 2016).

Kolb, A. Y. and Kolb, D. A. (2010) ‘Learning to play, playing to learn: a case study of a ludic learning space’, Journal of Organizational Change Management, 23(1), pp. 26-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09534811011017199. Available at: http://learningfromexperience.com/research/ (Accessed: 18 November 2016).

Lupton, E. and Miller, J. A. (1993) The ABC’s of [triangle, square, circle]: the Bauhaus and design theory. London: Thames and Hudson.

Nurse, K. (2006) ‘Culture as the fourth pillar of sustainable development’, Small States Economic Review and Basic Statistics, 11, pp. 28-40. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.183.5662&rep=rep1&type=pdf (Accessed: 18 November 2016).

Park, H. and Benson, E. (2013) ‘Systems thinking and connecting the silos of design education’, International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education, Dublin Institute of Technology, Ireland, 5-6 September. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/10058487/SYSTEMS_THINKING_AND_CONNECTING_THE_SILOS_OF_DESIGN_EDUCATION (Accessed: 18 November 2016).

Pinckney, S. (2013) ‘Simplicate this! Bob’s 3 Sustainability models’, The Huffington Post blog, 2 December. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/suzanne-pinckney/simplicate-this-3-sustain_b_4026424.html (Accessed: 16 November 2016).

Postma, C. and Stappers, P. (2006) ‘A vision on social interactions as the basis for design’, CoDesign: International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts, 2(3), pp. 139-155. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15710880600888527.

Potter, N. (2002) What is a designer: things, places, messages. London: Hyphen Press.

Rawsthorn, A. (2013) Hello world: where design meets life. London: Penguin Books.

Sanders, E. and Stappers, P. (2008) ‘Co-creation and the new landscapes of design’, CoDesign: International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts, 4(1), pp. 5-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875068.

Sterling, S. (2012) The future fit framework: an introductory guide to teaching and learning for Sustainability in HE. York: Higher Education Academy. Available at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/resource/future-fit-framework (Accessed: 18 November 2016).

Sterling, B. (2005) Shaping things. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Suda, B. (2010) BBC Newsnight: information graphics. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q2Wnu1SOhKs (Accessed: 16 November 2016).

Sueda, J. (ed.) (2014) All possible futures. London: Bedford Press.

Ryan, A and Tilbury, D. (2012) Education for Sustainability: a guide for educators on teaching and learning approaches. Gloucester: University of Gloucester. Available at: http://efsandquality.glos.ac.uk/toolkit/EfS_Educators_Guide.pdf (Accessed: 18 November 2016).

Yousefi, B. H. (2012) ‘Design process model from a designer’s research manual’, BHY - Web Platform of Bahram Hooshyar Yousefi, 14 September. Available at: http://bhyousefi.com/?p=105 (Accessed: 16 November 2016).

Charlie Abbott is an Associate Lecturer on the BA (Hons) Graphic Design course at Camberwell College of Arts. He is part of work-form, a graphic design studio based in south London.